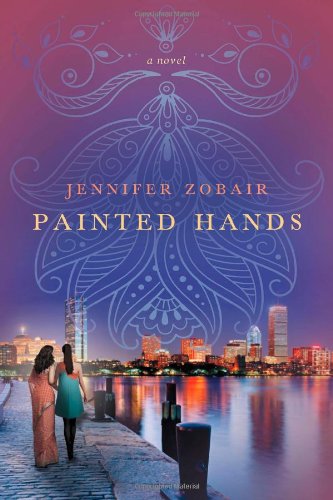

[amazon_link id=”1250027004″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ] [/amazon_link]Title : Painted Hands

[/amazon_link]Title : Painted Hands

Author : Jennifer Zobair

Genre : South-Asian Fiction

Publisher : Thomas Dunne Books (Macmillan)

Pages : 336

Source : Netgalley/Publisher ARC

Rating : 3.8/5

Painted Hands is about three young women struggling with their life and religion. Zainab Mir, Amra Abbas and Rukan are three young Muslim women born and brought up in the US. All three are fairly modern and moderate Muslims. While Rukan’s story is touched upon, this novel is mainly about Zainab, Amra and Hayden – Amra’s office colleague. Amra is a lawyer, working unearthly hours at her law firm in the hopes of making partner. Zainab is a political worker, and the main person behind Republican Senator Eleanor Winthrop-Smith’s election campaign. Hayden, also a lawyer, comes from a troubled family background and is struggling with her own faith, and attraction towards Islam.

Both Zainab and Amra have tireless zeal for work; their careers are an important part of their lives. But they also come from cultures which are traditionally patriarchal, where a woman is expected to kow-tow to the demands of family and household first and foremost. Zainab, who is scorned by traditionalists as an aberrant Muslim, for wearing supposedly skimpy clothing, and consorting with supposedly irreligious people, has given up trying to prove her faith; she does what she likes, and everyone else can lump it. Amra on the other hand, is in love with Mateen, the son of family friends, and finally marries him. Post-wedding, she has a hard time being the “good” wife and the willing-to-go-the-extra-mile lawyer. Hayden is more and more attracted to more-than-casual-acquaintance Fadi, and distanced by Amra, and influenced by religious zealots like Fareeda, takes a step which will change the course of her life.

This is a very well-written book. The characters are believable. Zobair treads the fine line of making them appear modern and progressive Muslims, rejecting fundamentalist, regressive notions, but still maintaining love and respect for their culture and heritage. We do not generally get to read of such moderates, so it was quite a breath of fresh air to hear the views of these feminists. Apart from the religious aspect, the women in this novel struggle for basic equality, because that is what it boils down to – the idea that one’s life is one’s own and not subject to expectations – cultural or otherwise. We can call gild it, give it the superficial once-over and declare ourselves progressives, but are we really? In real life there is no absolute black and white, but a lot of grey. Zainab, Amra and Hayden find that out once they step into the system, Amra by marrying into it, Zainab by thwarting it and Hayden by idolizing a religion she does not understand.

I liked the fact that Zainab and Amra stood strong even when under pressure. Zainab has the courage of her beliefs, as is evidenced by her sparring with the religious fundamentalists of a mosque she goes to. She identifies as a Muslim but does not kowtow to the regressive tenets the mullahs advocate; she comes under attack from both Islamic and Christian conservatives – one thinks her not Islamic enough, and the other finds her too Islamic. Amra, meanwhile, puts up a brave face under pressure but begins to suffer, physically and mentally, under all the conflicting demands – I felt for her.

The women in this book are Muslim feminists, a term so rarely heard in mainstream media, it might as well not exist. Zainab, Amra, Rukan and Hayden wanting no more than to live their lives as they see fit, are buffeted by unreasonable demands; society and family send out subliminal diktats on their duties as “good” women – how to look pleasing and non-threatening, appear ready to obey, and drop all their aspirations and worked-for-goals when told to do so. Feminism is often thought to be “outside” the system, but there must be a middle ground, or so Amra believes – a way to be true to oneself and one’s dignity, while maintaining familial and personal relationships. It is a hard question to tackle and there are no easy answers, which makes this book even more worthwhile to read.

There are a few sprinkled oddities in the book – like the fact that Amra’s NYU professor mother, for all her education and joy in her work, appears to be rather diminutive in the assertion of her (progressive?) beliefs, and very ready to “persuade” Amra into matrimony, something that Amra’s career cannot handle just then, or her annoying habit of prefacing each sentence she says to Amra with “beti”. Beti mean daughter, but does one address one’s daughter with that, every single time?

“Painted Hands” was an interesting read, a look-see into the other, little-known side of Islam, from the female point of view. Recommended.