[amazon_link id=”1400066492″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ] [/amazon_link]Title : The Village

[/amazon_link]Title : The Village

Author : Nikita Lalwani

Genre : Contemporary

Publisher : Random House

Pages : 256

Source : Netgalley/Publisher ARC

Rating : 3/5

This book has an interesting setup. Ray Bhullar is a film director with the BBC, in India to make a documentary about Ashwer, an open prison community. With her are a producer, the blonde Serena, and a presenter, Nathan. Ashwer is interesting to them because it is the only open prison system which is succeeding. It is a little village comprised of convicted murderers and their families. One member of each household has committed a murder. In this open community they live almost like they would in the free world. They live in homes with family members – spouses, children, parents and seek work for their livelihood. They are permitted to go outside the community for work in the daytime but must return at dusk. It is seen as a model program to assimilate criminals back into society, and it appears to work, since no resident of Ashwer has yet attempted to run away or commit a crime.

Ray is British-Indian, can speak some Hindi and is fairly conversant with local traditions. Serena and Nathan are total outsiders with no such advantage. The other relatively major character in the book is Nandini, a convicted criminal herself, but one who acts as counselor and is continuing her education in the local university. Nandini and Ray strike up a tenuous friendship.

The book traces Ray’s attempts to familiarize herself with the community, getting people to open up about their thoughts and experience at Ashwer. She wishes to make an honest documentary about Ashwer and it’s people, but Serena and Nathan and indeed Ray’s boss (whom she talks to on the phone) have other ideas. The book’s plot then turns into a question of morality – that of keeping honest in the times of scandals and scoops and exclusive, breaking news. Who really is the villain here – the villagers who are convicted criminals and seen to be unfit for release into society or the three filmmakers who seemingly will sacrifice every scruple to get the “money-shot”?

This book didn’t work for me. Although Lalwani does a good job of portraying locales and atmosphere, I did not like Ray, Serena or Nathan, and it is hard to care about people you don’t like. Ray is the director, but seems weak and wishy-washy, unable to stand her ground until it is too late. While I sympathized with her difficult position with her work-mates, I was frustrated by her utter naivete – why was her character such a babe in the woods? Did her work in the media, her 27 years on capricious earth teach her nothing? Ray’s character seemed very unrealistic to me. Serena and Nathan were plain unpleasant – she was cold, unfeeling and critical, and he a slimy, sinister no-good loser spewing negativity. The plot itself seemed jaded, very been-there-done-that; it might be that I have watched many films with just this kind of fight for integrity.

The book never quite took off. I kept waiting for things to get to a head, but they never did. I realized that the journey was the destination, so to speak, but it never quite got interesting enough.

[/amazon_link]Title : Murder in Passing

[/amazon_link]Title : Murder in Passing

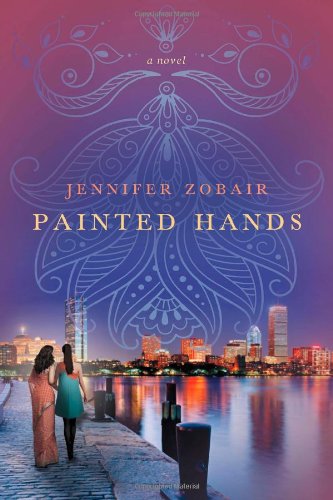

[/amazon_link]Title : Painted Hands

[/amazon_link]Title : Painted Hands [/amazon_link]Title : White Trash

[/amazon_link]Title : White Trash [/amazon_link]Title : Pastor’s Wives

[/amazon_link]Title : Pastor’s Wives

[/amazon_link]Title : The Honey Thief

[/amazon_link]Title : The Honey Thief

[/amazon_link]Title : Equal of the Sun

[/amazon_link]Title : Equal of the Sun